Commonpaths Project Transdisciplinary Meeting Report for research partners

1 The Project

This report synthesizes the output of the first Transdisciplinary Meeting of the CommonPaths project the 18th of October 2024. The CommonPaths project is a research initiative backed by the Swiss National Science Foundation. It brings together researchers from Switzerland, Ghana, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands and Austria to explore urban commons and their contribution to sustainability.

What are “ urban commons”?

We define “urban commons” as a resource that is self-managed by a community of users in an urban setting. One example for urban commons are housing cooperatives that operate on a cost-rent basis. These cooperatives provide affordable housing possibilities without a profit imperative, promoting de-commodification in the housing sector. Other examples include community-supported agriculture or urban gardening initiatives.

Commonpaths-Project

The Commonpaths-Project focuses on how these commons can help reduce our reliance on market-driven systems for provisioning of (essential) goods such as housing, food, and green spaces, a process known as de-commodification.

At the core of this project is the value of “transdisciplinarity”. This means blending knowledge from different scientific fields and from community members and policymakers. By working together, we can tackle complex urban challenges more effectively and ensure that the knowledge created is actually of interest to stakeholders.

To enable this transdisciplinary exchange, the Commonpath-project organizes learning platforms. These platforms bring together diverse voices to discuss research findings and their societal relevance.

First Transdisciplinary Meeting

The event of the 18th of October was the first such event where reserchersresearchers from the CommonPaths project met for the first time with members of urban commons from Switzerland.

During the meeting, CommonPaths researchers presented their research perspectives on urban commons. The meeting was structured around three key themes related to topics and challenges that urban commons potentially face in their practice: “Access to land”, “Self-Organization” and “Transformation of societies”. The researchers gave insights on each theme in short presentations of 15-minutes. Following the morning inputs from researchers, participants from collectives formed groups with researchers in the afternoon to openly discuss and reflect on their experiences.

| Name | Organization | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [undisclosed name] | Uniterre | [undisclosed email] | |

| [undisclosed name] | Terrain Gurzelen | [undisclosed email] | |

| Matthias Meier | Solawi-Mitglied | [undisclosed email] | |

| Maggie Carter | La Soliderie | maggiecarter@lasoliderie.ch | |

| [undisclosed name] | Schloss Glarisegg / GEN suisse | [undisclosed email] | |

| Cathérine Mathez | La Meute Coop | Catherinemathez@gmail.com | |

| [undisclosed name] | Winkelhalden | [undisclosed email] | |

| Uli Amos | Coopérative Equilibre / Genossenschaft Equilibre | uli.amos@cooperative-equilibre.ch | |

| Frederica Viret | Pilote CODHA | fredoricaf@yahoo.com |

| Name | Degree | |

|---|---|---|

| Sabina Pedrazzini | PhD student | sabina.pedrazzini@unibe.ch |

| Pambana Basset | PhD student | pambana.bassett@unibe.ch |

| Samuel Agyekum | PhD student | samuel.agyekum@unibe.ch |

| Vincent Aggrey | PhD student | vincent.aggrey@unibe.ch |

| Johanna Gammelgaard | PhD student | johanna.gammelgaard@unibe.ch |

| Adrien Guisan | PhD student | adrien.guisan@unibe.ch |

| Simon Gude | Intern | simon.gude@unibe.ch |

| Deniz Ay | Post-doctoral researcher | deniz.ay@unibe.ch |

| Tianzhu Liu | Post-doctoral researcher | tianzhu.liu@unibe.ch |

| Lilla Gurtner | Post-doctoral researcher | lilla.gurtner2@unibe.ch |

| Jean-David Gerber | Professor | jean-david.gerber@unibe.ch |

| Bettina Hanstein | Translater | bettina.hanstein@gmx.de |

Structure of the report: The report is structured by the topics the TD-meeting focused on. For each theme, a summary of the presentations and workshops outputs is given.

| Morning session | Afternoon session |

|---|---|

| Presentation of the Project by Jean-David Gerber | |

| Presentation Access to land, Section 2.1.1 by Tianzhu Liu | Workshop / Discussion Access to land, Section 2.1.2 |

| Presentation Self-Organization, Section 2.2.1 by Sabina Pedrazzini | Workshop / Discussion Self-Organization, Section 2.2.2 |

| Presentation Transformation, Section 2.3.1 by Lilla M. Gurtner | Workshop / Discussion Transformation, Section 2.3.1 |

This report also aims to set the stage for continuing dialogue and collaboration between the involved collectives, initiatives and researchers. As an outlook for this endeavor, we encourage circulation of this report across members of the collectives and welcome follow-up questions regarding the content, as well as proposals for organizing joint events. The Commonpaths-Project can be contacted via: commonpaths@cde.unibe.ch

2 Thematic Inputs

2.1 Access to Land

Tianzhu Liu, Urban Planner, Postdoc researcher, Institute of Geography, University of Bern

2.1.1 Morning: Presentation

“le principal problème c’est le terrain”

The presentation of Tianzhu Liu aimed to shed light on how commons initiatives can access to land for food, green spaces, and housing provisioning, and how they overcome barriers in the current system in Switzerland. This is not favourablefavorable to commons initiatives: “The principal problem (of launching a collective) is land” (Le principal problème, c’est le terrain). During our survey on urban commons initiatives, Oone interviewee from a housing cooperative in Switzerland told the commonpaths team as such. Land is a precious yet scarce resource for commons initiatives, especially in urban and peri-urban settings. Key challenges include limited land availability, high costs, lack of information on available land, and insecure land tenure. Farming collectives also face legal constraints.

Addressing the problem of access to land

In response, commons initiatives employ strategies such as relying on public authority support and forming peer networks to identify and get access to land. Although public authority support – especially municipal support – is significant, only a few municipalities apply active policies to systematically support commons initiatives, such as providing municipal land to collective farms. The presentation emphasizes the importance of these approaches and invites further discussion to refine strategies for overcoming these challenges in terms of access to land.

2.1.2 Afternoon: Workshop

The afternoon discussion occurred mainly between two members of commons initiatives, Tianzhu Liu, Adrien Guisan, and Jean-David Gerber, focusing on access to land for housing and food production. Both recognized the essential need to connect food-production and -consumption, as well as the potential to connect housing cooperatives and agroecological farming practices.

Legal constraints

The group first discussed the legal constraints from Swiss rural land law (Loi fédérale sur le droit foncier rural or LDFR in French, Bundesgesetz über das bäuerliche Bodenrecht or BGBB in German) for new farmers without family farming background and farming collectives. On the one hand, the law hinders farming collectives’ access to land, On the other hand, it also protects farming land from speculation. Recognizing the beneficial side of the law, participants address the possible pathways to find local solutions, especially seeking support from the municipality.

The role of municipalities

The discussion showed that local municipalities can make their land available for collective farming. However, this is complex: there is often a lack of transparency, a reluctance to allocate land for farming, and a tendency to favor established farmers instead of new entrants and collectives. The members of commons initiatives highlighted that the major issue is not necessarily ownership, but a) the guarantee for farming collectives to have tenure security in using land and b) the rights to receive subsidies. Finally, the participants highlighted that in order to provide a favorable context for commons initiatives to get access to land, the there is a need to build broader support by engaging the public, sharing inspiring examples, and examining international practices (such as community land trust), albeit with awareness of the unique Swiss legal and economic context.

2.2 Self-Organization

by Sabina Pedrazzini, PhD candidate, Social Psychologist

2.2.1 Morning: Presentation

When talking about cooperatives who self-manage a common resource, self-organization is a key aspect to consider. Indeed, it directly depends on the members of the cooperative, and it determines the collective activities’ efficacy.

In the initial phases of the research project, Sabina Pedrazzini conducted preliminary interviews, which allowed her to identify different characteristics of cooperatives that impact self-organization (group-size and –composition), and challenges that are often encountered (how to motivate members to engage in the self-organization activities).

Group size

The number of members of a cooperative can greatly impact self-organization, and there are challenges associated with both a too large and a too small group.

On the one hand, in large groups, members can’t know all other members, which increases anonymity and decreases trust. Moreover, others’ actions are less transparent; it is hard to know exactly who did what. This context reduces individuals’ motivation to cooperate, because individuals perceive their personal efforts for the common good as less visible and impactful.

On the other hand, in small groups there is a greater risk of having the so-called “pioneer burn-out”, i.e. a few people undertaking a larger share of work than they can sustain in the long run. Moreover, in small groups individuals always work and discuss with the same people, increasing the risk of interpersonal conflicts. Finally, even small conflicts between members represent a greater risk for the overall group dynamic in small, rather than large, groups.

A strategy often observed in large cooperatives to address this issue is to create smaller sub-groups to alleviate the challenges associated with too large groups.

Group composition

A group’s composition can also have an important impact on self-organization. During the preliminary phases of the research, Sabina Pedrazzini observed that cooperatives’ members tend to be quite homogeneous, especially in terms of socio-economic status, educational background, and values (i.e. willingness to find an alternative lifestyle). This homogeneity usually facilitates cooperation, since individuals trust more easily people who are similar to them. However, there was often a willingness, on the part of the cooperatives, to grow in size in order to have a greater social impact. This would inevitably lead to a more heterogeneous group of members. For this reason, when including new members, it is essential to consider how this new diversity could impact the organization of the cooperative.

Challenges: how to motivate people to engage in the self-organization process?

Finally, the most observed challenge is the lack of motivated people taking part in the activities of the cooperative. These tasks require time and are often done on a voluntary basis. Not everybody has the willingness or the material and time resources to engage in such activities. For this reason, cooperative must find alternative ways to motivate their members to get more involved. For instance, they could highlight the personal benefits that members could have if the cooperative was more active.

2.2.2 Afternoon: Workshop

The workshop was structured in two parts:

Discussion about self-organization

What does it mean in practice? What are the members’ favorite aspects (i.e. which activities within the cooperative they enjoy the most)? What are the most frequently encountered challenges?

Summary:

Self-organization is often associated with inter-personal relationships (cooperation, learning, collective decisions, etc.). This confirms the importance of considering the group’s characteristics to find the optimal way to self-organize.

The favourite aspects mostly revolve around projects’ realization/concretization. This is linked to the concept of “collective efficacy” (presented later in the document), according to which individuals who perceive the activities of the cooperative as effective should be more motivated to take part in self-organization. However, this also highlights the importance of finding a way to keep motivation high even in periods where the cooperative is not actively implementing any project.

Among the challenges, the difficulty of taking collective decisions that satisfy everyone has been often mentioned. This highlights the importance of setting structures that facilitate this process (e.g. only the majority, and not the total consensus, needed to approve a decision, etc.).

Three factors that theoretically predict the involvement in self-organization

Participants reflected on their personal experiences and linked them to three concepts that, according to social psychological theories, influence the involvement in self-organization in a commons:

Every individual is part of several “social groups”, such as the group “women”, “students”, … These group-belongings are part of our identity, and therefore define us. Research in social psychology showed that there are individual differences in the strength of the identification to the group, and this defines to which extent people care about the group’s well-being. Moreover, the more we identify with a group, the more we feel similar with other members of the group.

This is also valid for the group “member of the cooperative X”: people who are much involved in the organization of the cooperative probably identify more as members. Conversely, improving members’ social identification with the initiative should increase their motivation to engage.

The discussion identified aspects that can enhance social identification (social identity linked to the city, i.e. engagement in a cooperative to improve “our” city, identity created through activities specific to the community / collective work experience, external adversaries as help to foster a social identity within the group) and aspects that hinder social identification of members (too much individualism, give-and-take mentality between members and the initiative, declining identification in people engaged in the cooperative for a long time). The initiatives present at the workshop identified actions to foster social identity such as taking group pictures, organizing parties to celebrate the cooperative’s achievements, inside jokes among members, fun activities, distinctive signs (t-shirt, …), encouraging the interactions between members.

Every individual can have different values, ideology and moral principles. This is also the case regarding the attitudes toward taking part in the organization of the cooperative: for some people, to contribute to the cooperative’s well-being can be seen as a moral obligation, while other people don’t perceive this obligation.

During the discussion, participants raised two levels of morality: the first, broader level concerns the need to act to protect human rights, while the second level concerns the moral obligations toward other members of the cooperative, and the respect of engagements. Morality was also perceived as an individual characteristic, since participants often mentioned that members with a stronger moral responsibility did a bigger amount of work. Moreover, the feeling of responsibility toward the cooperative can improve when individuals are strictly linked to their projects. Finally, when new members join, sometimes they must learn what it means to have responsibilities toward the cooperative.

This concept defines the extent to which individuals perceive the group’s actions as being effective to lead towards a goal. This perception can vary between individuals and determines their motivation to engage in the self-organization process: the more individuals think that their group will efficiently attain its goals, the more they are motivated to act and to take part in the groups’ activities.

During the discussion, the fact of realizing projects together was often mentioned as example of collective efficacy. This could concern the building of new locals for the cooperative, publications to increase people’s knowledge about the cooperative, or having small projects that slowly come together for a bigger realization. Moreover, participants also mentioned that having a team of people with different knowledges and experiences also improved the feeling of collective efficacy, and that bringing people together to work on a project could foster this feeling. Finally, the fact that a project doesn’t turn out as planned, or doesn’t reach the goals initially set, could reduce the feeling of collective efficacy.

2.3 Transformation of societies

Lilla Gurtner, Postdoc, Psychologist & Sustainability Researcher

2.3.1 Morning: Presentation

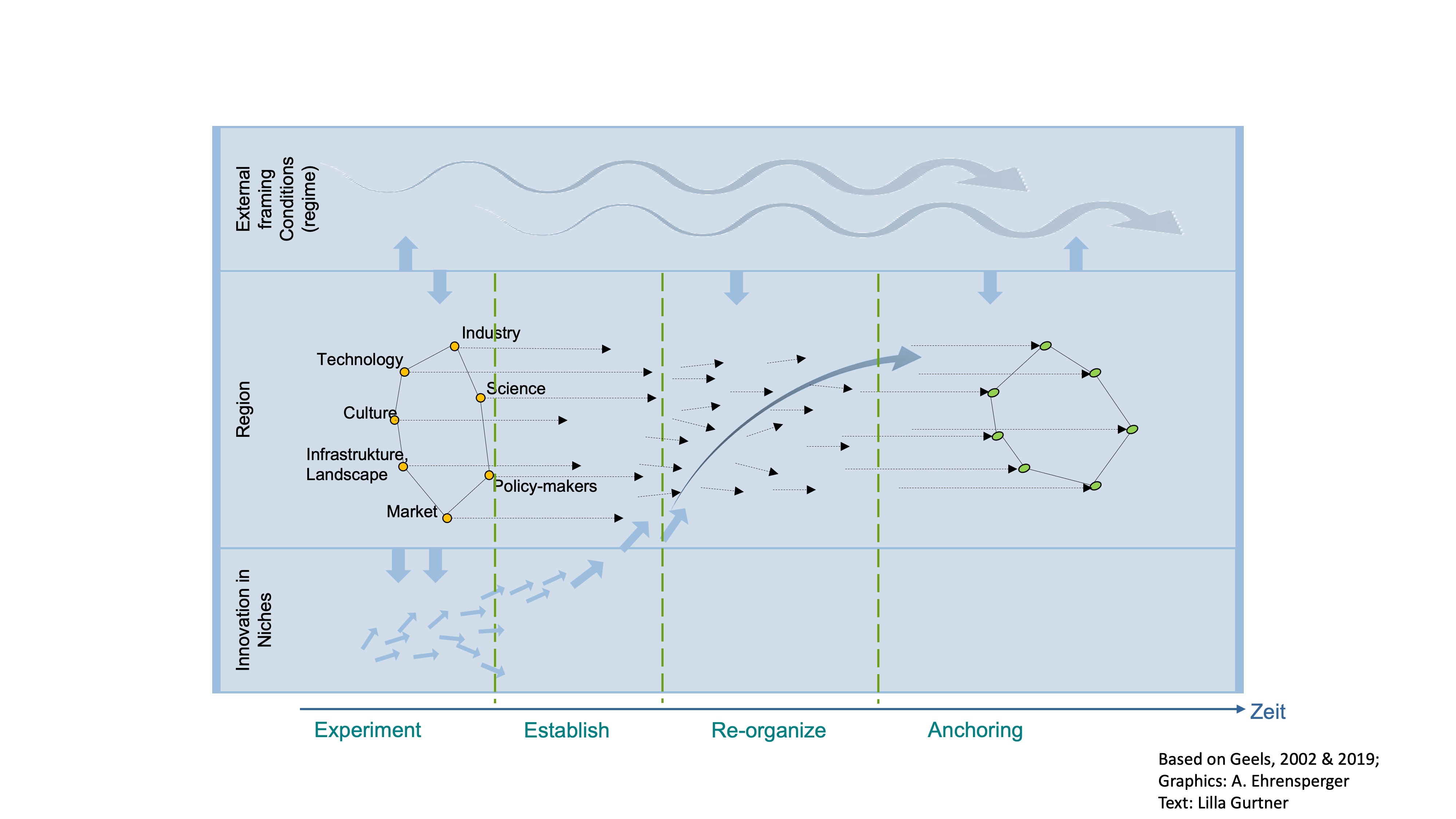

Commons initiatives are crucial in a sustainable society, at least as they are conceptualized by Degrowth and Postgrowth thinkers1. However, it is not so clear how commons initiatives contribute to getting from here towards a more sustainable, postgrowth society. To help find an answer, the presentation of Lilla Gurtner started with a theoretical framework of large-scale transformation of socio-technical systems, i.e. energy provision systems, or also adoption of new technologies like the Internet by Geels & Ayoub2.

A Model for Societal Transformation

According to this “multi-level-perspective”, large-scale transformation of societies can come from “niches”: Protected spaces in a society shielded from demands, for example, with respect to profitability. In these niches, different initiatives experiment with new arrangements and possibilities (technology example: powering a house with solar energy, social innovation example: new forms of participatory decision-making). Some of the initiatives fail and others find arrangements that work well. Some of these well-working initiatives can coalesce into a stronger movement with a shared vision and growing intermediary network organizations (establishing). If then, on the big scale, there is a window of opportunity (like soaring energy-prices after the beginning of the war in Ukraine, or a perceived alienation of people from desicion-making) and niche-level actors are ready, the technologies and practices from the niches can spread to the more “mainstream” level of society (new ordering). As the technologies and practices are taken up, they are institutionalized and change the general societal setup (embedding/ancoring).

How commons can lead to change

Based on a review of the scientific literature, Tianzhu Liu, Johanna Gammelgaard and Lilla Gurtner distilled three main ways by which commons initiatives are argued to lead to change: by making (prefiguration, experimenting with the future in the here and now), by networking with others (passing on knowledge) and by fostering inner tranformation (changing conceptualizations of “the good life”). With this presentation ended the morning session.

2.3.2 Afternoon: Workshop and discussion

The workshops (held in French and German) focused on how members of commons initiatives perceive and experience their own role in societal change: are they aiming at social change with activities? What kind of changes have they witnessed themselves based originating from their work? And do these changes reflect the three strategies emerging from scientific literature? In two sessions of rich discussions, it became clear that all participants agreed that their initiative was at least somewhat interested in contributing to social change (with one exception) and that all had witnessed some change as a result of their actions. All these changes were categorized as related to one of the three strategies (making, networking, inner transformation) except for one: organizing advocacy that ultimately changed the energy price of a neighborhood. Interestingly, this change was brought about by the initiative that was not so interested in advancing social change in the first place. Thus, the change-strategies resonated with participants and were enriched by actual examples for each of those. Finally, we collected perceptions of which strategy was most effective, and which one was most used.

Effective and broadly used strategies

Interestingly, participants pervieved other initiatives as predominantly persuing making and networking strategies in general, but thought that inner transformation was the most effective strategy to achieve societal transformations. Discussions then lead to the thought that a) making and networking are more observable than inner transformation and that b) making and networking can lead to inner transformation. Thus, the three strategies are not mutually exclusive, and they can even reinforce each other.

3 Conclusion

Focusing on the three thematic foci of access to land, self-organization, and societal transformation, this Transdisciplinary Meeting reveals important takeaways.

In a nutshell, in challenges around access to land, the major issue is not necessarily ownership, but the tenure security in using land and the rights to subsidies. For securing tenure, it is essential to build broader support by engaging the public, sharing inspiring “best practices” and examining international practices with awareness of the unique Swiss legal and economic context. On the subject of self-organization, social identity, morality, and collective efficacy are the three main pillars that represent the challenges that urban commons initiatives face. Self-organization is closely related with inter-personal relationships of cooperation, learning, and collective decision-making. A good grasp of group characteristics is key for finding optimal ways for self-organization. Finally, on societal transformation, strategies of making, networking, and inner-transformation can be ways in which initiatives contribute to social change, while witnessing some tangible real change themselves in their communities through their actions.

We would like to thank all participants for their time. This one-day meeting for Transdisciplinary Exchange was a great opportunity to exchange perspectives from research and practice, as well as establishing new connections across commoners from different initiatives and sectors. The meeting also had a key objective to contribute facilitating bilingual exchange across collectives, which is particularly a challenge in Swiss context. For this, we would like to thank our translator Bettina Hanstein who smoothly switched between languages and ensured that all participants could understand each other regardless of language levels. In collaboration with Commonpath’s partner organization Sanu Durabilitas, we are looking forward to continuing this fruitful dialogue to ensure societal relevance of our research.

Footnotes

Barlow, N., Regen, L., Cadiou, N., Chertkovskaya, E., Hollweg, M., Plank, C., Schulken, M., & Wolf, V. (Eds.). (2022). Degrowth & strategy: How to bring about social-ecological transformation. Mayfly Books.↩︎

Geels, F. W., & Ayoub, M. (2023). A socio-technical transition perspective on positive tipping points in climate change mitigation: Analysing seven interacting feedback loops in offshore wind and electric vehicles acceleration. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 193, 122639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122639↩︎